Gladys made them bag lunches, a ham and cheese sandwich, a bottle of orange juice, Oreo cookies wrapped in napkins.

“I ain’t gonna picnic in no graveyard,” Lake said in the car.

“It’s real beautiful up there. Willy and me went up a lot.”

Out of the city, on 299’s casual sweep west to the mountains, she lay her head on the passenger window, let the hot wind stream her hair.

Lake stretched out on the backseat. “I never saw no country, real country, till they sent me. I thought needle parks was the country. Needle parks you know what’s up. Makes me nervous all these trees.”

“This is America, Lake,” said Mona.

“America makes me nervous.”

They passed through Shasta. “What’s with that?” Lake asked.

“Ghost town.” She cast a sad eye on the historic red brick buildings. “Willy and me, we.”

“Ghost towns, trees, wild wild west. What the fuck next?” complained Lake.

“A cemetery,” said Jimmy, anxiety threading his chest, relieved and intensified by Mona’s breasts, which swelled upward against her blouse when she twisted into the wind. The blouse was easy to unbutton, that is if one unbuttoned it, that is if one wanted to, that is if one would, was allowed, invited. Jimmy the Rake had an unrakish principle: let the woman make the first move. It always worked and he was, by logic, never rejected.

An edge of broad water came to view. “Whoa! There, make a left,” said Mona, pulled her head in. Jimmy spun the car onto Kennedy Memorial Drive (a Kennedy Memorial Something all the way out here?) “Pull over, there’s a view.” She jumped out at the overlook. A kid, thought Jimmy, in a movie star bod. Not-quite-Norma-Jean.

Below them, Whiskeytown Lake filled a wan cup of rolling greenscrub and periodic stands of pine. On the jade water, a few weekday tourist-craft, a squat houseboat, men fishing. A speedboat on a base of white water roiled cross-stitched waves behind.

“Willy used to come up here with his Uncle Dunc,” said Mona. “He said it was like watching dinosaurs.”

“What was like watching dinosaurs?” said Jimmy.

“The heavy equipment, bulldozers, like that. They had to dig it out to hold the water. He was a little boy.” She watched the speedboat turn, tear through its own bargello waves. “Nine years ago. He was just a little boy nine years ago.”

“So where’s Whiskeytown?” asked Lake.

“Under there.” She pointed northwest. “See the bridge?”

“Under water?”

“It was a dump. They moved everybody out. Dug up the cemetery.”

“The one we’re?” said Jimmy. His chest ached with the unsubtle contradiction that he was at once on a picnic, a pilgrimage to a tomb, a vacation trip, and an underground railroad journey with a man who could, under military law, be shot for it. Above him there was too much sky.

“Didn’t want them dead folks to drown,” said Lake.

“How much farther?” Jimmy asked Mona.

“Couple miles.”

He would have passed the cemetery had Mona not touched him (on the thigh), pointed to a graveled open space by a grove of thin scraggle pines, under which lay sheltered a what?

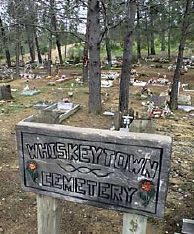

They slammed the doors. Mona started toward the entrance sign, a wooden rectangle inscribed WHISKEYTOWN CEMETERY in the style of woodcraft sets that come with a soldering-iron to scorch your name on blocks. Lake and Jimmy stood by the car. Mona paused. They were alone. The car engine, cooling, ping’d. Lake and Jimmy absorbed the sight.

At first it looked like a yard sale or a lumber yard where lawn ornaments are sold; adorning brightness outshone the grave stones. Jimmy and Lake stepped forward with caution, Mona astonished by their astonishment.

“Neat, huh?” she said, passed by the sign, headed in Willy’s direction, but Jimmy and Lake took their time, paused at graves that seemed in two categories: ancient and new. OUR BABY, read a square pillar, Born Jan. 7, 1862, Died, Jan. 12, 1862. Plain dirt around it. OUR BABY’s family long gone.

“Look here,” said Lake. A stone rectangle in the ground,

GEORGE MATEE

UNK 1907

on which someone had placed a recently deceased carnation.

Mona walked ahead. Lake and Jimmy stopped at a grave that might be the fifth hole of a miniature golf course, or a tiny backyard paved in astroturf.

Graves marked by yellow windmills, plastic tulips, purple and red, windchimes of rusted forks and spoons.

A grave outlined with handpainted rocks.

Graves encapsuled by molded scalloped garden border strips.

Graves with photographs newly renewed, a letter from a teenage girl to her mother underneath the ground, the letter framed in plastic, I miss you so much Mom.

A gravestone fashioned from a piece of mining machinery.

A homemade stone like a rounded upright slab of sidewalk, the survivors’ handprints, large and tiny, in the cement.

A chainsaw buried upright, the deceased’s name stenciled between the rows of teeth.

A cradle grave lined with the stuffed toys of the child beneath.

Porcelain animals: deer, cats, dogs, sheep, antelope. Soapstone ducks, geese, rabbits.

Twirling fans on sticks that kids win at carnivals for the pingpong ball throw.

The inscription: #1 MOM.

A border of tequila bottles.

Pink bunnies, some stuffed, some plastic.

A grave surrounded by a white picket fence, as the occupant’s house must have been.

Homilies and messages: death be not proud, life is short, we love you dad, say hi to granma for us, we hope you’re happy now.

Each grave its baliwick, its jurisdiction, its personality. A republic of shrines, ungoverned.

Mona stood at Willy’s home in the neighborhood, marked by an upended dozer plow, an odd spike protruding from its upper end, the blade inscribed with his identity, Wilson Pickett, his lifetime 1950-1968, his encomium, killed in Vietnam, a real hero, we’re proud of you Willy. Fastened to the blade beneath these words, a laminated 8 X 10 color photo: Willy in uniform, head and shoulders, fatigue cap.

Jimmy looked at himself in the photo. Himself looked back.

Mona looked at Jimmy looking at himself in the photo. “You see?” she said.

A plastic geranium bouquet dangled from the spike on the plow blade.

“Oh fuck!” said Mona. She reached over the border of the grave— which Jimmy saw was a spiral of three-inch-high, toy-sized razor wire, the perimeter of Willy’s final base — and plucked up a white card. “Some fucker keeps putting this here.” Handed it to Jimmy. On one side:

They don’t want you.

They don’t need you.

You have to be a fool

to die in Vietnam

on the other

There are two kinds of fool:

A deliberate fool.

An accidental fool.

Which are YOU?

She bit her lip, twirled to see if the card-bearer was lurking in the pines. “That fucker! That fucker!” Jimmy passed the card to Lake. “You know who it is?” he asked her.

“No. Some asshole antiwar. The Blood Lady. I don’t know.”

“Willy wasn’t a fool,” Lake said. “The Colonel got him killed was the fool. You know Willy carved a peace symbol on the firebase with his Plow.”

“He never wrote about that.”

“He didn’t have time. It was a heavy scene.”

They stared at the grave. Jimmy couldn’t shake the impression he was viewing a firebase from a helicopter.

“I apologize for whoever put the card,” said Jimmy. “We got all kinds in the movement. Some are mean and fucked-up. Willy doesn’t deserve this.” He thought of the woman at the Induction Center screaming baby-killers. He should have, he didn’t know what, then, to her.

“I’ll write his folks a letter,” said Lake. He didn’t say from Canada. “I’ll tell them what kind of guy he was.”

Jimmy knelt close to the Rome Plow blade to get a good look at himself. What was on Willy’s mind when the photo was taken? Jimmy thought he ought to know. All he saw was a young man neither happy nor sad who had no idea how short the rest of his life would be.

“You know people in town who never thought twice about him before, now they’re proud they knew him.” Jimmy couldn’t tell if Mona intended irony, or knew what irony was. “His coach has a photo of him in his office, which he didn’t when he was.”

Nothing left to do but leave. Lake suggested they eat at the overlook. Mona followed them to the car, was the last to step in, screamed.

The men piled out, ready to rumble with snakes, bikers, MPs, the FBI, KKK. Jimmy yanked the keys from the ignition, went for the tire iron in the trunk.

Mona pointed back to where they’d been. A short man stood by Willy’s grave.

“The guy. Who puts the cards. Hey you!”

Lake held her by the elbow while Jimmy scrambled around the car.

The man’s back was to them. His hair was frozen lava, black.

“Wait,” said Jimmy. “That’s not him.”

“How do you know?” She tried to squirm from Lake’s grip. “You don’t live here, you don’t know. Hey you! What you doing!”

The burnt man was far enough away. Don’t turn around, please, pled Jimmy.

Dwight knelt. Even at that distance, they saw his shoulders shake.

“The card guy wouldn’t do that,” Lake said, released her arm, ready to pounce if she ran.

“How’d he get here?” she said. “There’s no car.”

“He hiked,” said Lake. “He parked his car somewhere else.”

“Who is he? I know his friends. He don’t look familiar.”

“People change,” said Jimmy. “You said he had friends now that he didn’t before. Come on. Hop in.”

“You sure?”

“I’m sure.” He turned on the ignition, imagined lava tears, and thought:

Where did they bury Dwight?