boys on the bus

Wilson Pickett’s crystal blue Dodge Dart cracked a bearing coming down from Trinity Lake and was laid up in some hippie’s transcendental no-rack garage in French Gulch with little hope of repair in a reasonable time. So it was either take the bus or walk to the Post Office to register for the draft.

No happy choice for a handsome boy who graduated 23rd in his class from Shasta Hi, captain of the track team, first baseman, spelling finalist, whose Levi Jean eyes called forth from his steady girl, Mona of the cantilevered breasts, the ultimate girl-statement of the 1960s or any other decade:

“Willy, when you look at me with those eyes, I’d do anything you want.”

Which got the response:

“Is that right, Doll?”

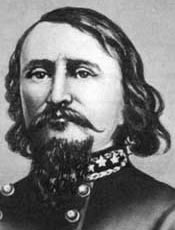

Willy’s name was a working man’s name, solid as picket fencing. His surname came from Woodrow Wilson, first president to mobilize our nation for total war, associated thereafter with idealistic internationalism, peace with honor, futility, stroke, paralysis, and death. His Christian name — according to a mailorder geneology service that sold family coats-of-arm based on similarities in spelling — descended to him from Maj. Gen. George Edward Pickett, a dapper flamboyant officer who wore his hair in long, perfumed ringlets, the man of Pickett’s Charge, destroyer of two-thirds his own division and all his colonels, the Beautiful Loser of Gettysburg.

Willy, embarking on his own losing streak, got on the bus.

Three stops later, a kid named Dwight, who Willy knew from senior chemistry class, sat in the seat next to him, carrying with the care and balance tendered by waitresses to trays with seven blue-plate specials, a one-quart metal hinged and clasped pinkrubber-rimmed glass canning jar containing a yellowish substance that quivered whenever the bus hit a pothole. Urine sample? Jello? Science project? Jellyfish? Pickled pee?

‘Dwight’ is a name people make fun of and Willy had, unless, of course, it preceded “D. Eisenhower”, but the Dwight in D. Eisenhower evoked reds, whites, and blues against a background image of the White House, whereas the Dwight next to Willy summoned images municipal, budgeted, dusty, thin, and greatless. Dwight On The Bus was to Dwight Of D-Day as parking regulations are to Supreme Court rulings, the family to the nation, the sheriff’s department (which they were approaching) to the Pentagon. Yet Dwight’s respect for the jar suggested a Nobel Prize chemical.

“Dwight?”

“Yeah. Hi.”

“Whatcha got there?”

“Nothin. Really.”

“Piss? Or what?”

“No. It’s.”

“I mean if it’s piss the doctor doesn’t really need that much. If it’s jelly preserves, you don’t have to carry it so careful.”

“No sir.”

“Dwight, we’re in the same grade. Were.”

“You were Captain of the Track Team.”

“Yeah but.”

“And Mona, wow.”

“Doesn’t make me Sir,” said Willy the democrat.

A municipal block jerked by.

“Napalm,” said Dwight, bowing toward his jar.

“What.”

“Napalm.”

The bus stopped. Two laborers, a maid, and a trash got off, a maid and a trash got on. The trash looked at the boys, the jar, said fags, lay down on the fullwidth rear seat. Next stop, Shasta County Courthouse.

“Dwight, would you like to get off and talk?” Willy felt a buzz of heroism coming on, like the first beer at a ballgame.

“You wouldn’t understand. I’ve thought about it a lot.”

“I’m sure you have.” Willy pulled the bell cord, which snapped without ringing.

“Gettin off, driver,” he said overloud. The maids scanned for teenager trouble. He pulled Dwight gently up with an arm round the shoulders. Fag. Down the steps.

“It won’t go off,” said Dwight. “It’s not nitroglycerin or anything.”

They sat on the grass before a shrine to Justice or something: a woman with no left hand and a bell behind her. Willy wondered what it would feel like to stir his finger in the jar on Dwight’s lap; would it be more like jelly, jello, motor oil, cum, honey, spit, hawkup, vanilla pudding.

“Are you looking to sell it?” asked Willy. “Like a military supply?”

“I’m gonna pour it on the draft board files,” said Dwight, and hung his head.

“That’ll make em sticky,” said Willy, who was not dumb but still mentally trapped along the lines of Elmer’s Glue and sperm.

“I cased the joint,” said Dwight. “I went in and asked them about their forms. The file cabinets they’re all behind the counter near the hall and the secretary she’s a regular linebacker so I thought during the event she might tackle me or hit me with a typewriter or something. I got embarrassed and left, went around the corner and there was this door, unlocked like nobody even cared. And wow there were the files, it was a door right on the hall where I could just go in and pour the napalm on the files and drop a match in.”

This was beginning to sound to Willy like a prerecorded confession, so he asked,

“For what?”

“To burn em up. Jeez.”

“Why?” Now Willy sounded dumb to himself.

“The war, man.”

“You’re not political.”

“Everybody’s political.”

“Your folks aren’t.”

“Mom’s in the union.”

Dwight’s mom worked with Willy’s mom in the bra factory. That wasn’t political, that was erotic. I mean a Bra Workers’ Union, D-Cup Underwire Divison? Mona got her bras through his mom’s employee discount.

Willy the counselor to troubled youth tuned his voice to calm and understanding.

“You’d be destroying private property, Dwight.”

“Public property, Wilson.”

“Taxpayers’ property, Dwight. The taxpayers make the money and own those files, see, and the right to property is protected by the Constitution. You’re getting yourself into federal law here, Dwight, which is unconstitutional.”

“The way I see it,” said Dwight Not Hardly Eisenhower, “some property has no right to exist.”

“That is plain crazy,” replied Willy, “I mean suppose some disturbed person like yourself decided my Dodge Dart had no right to exist. It would be as if America, which is our private property, had no right to exist. You got yourself in real trouble there.”

“If you was using it to kill people. If you were running little kids down with your car.”

“That goes to show,” said Wilson Pickett and he had him there. “If I use it to kill people, then they gas my ass, but do they punish my Dodge Dart? No they do not. They sell it or give it to my next of kin but they don’t punish it. Am I right? I mean the gun or knife Caryl Chessman used to kill that girl or whatever, where is it?”

“I don’t know.” Dwight rocked his napalm like a baby.

“At home with his Mom’s memorabilia I bet. You think a lot, Dwight, but you didn’t think about that. Property is sacred. What you’re doing is more illegal than killing. I got you there.”

“You got me there, Wilson.”

“Anyway why you? Why do you got to do it?”

“I done everything else. I graduated. I got a job.”

“Where?”

“Mini-Wash. Keepin stock.”

“Are you getting married?”

“No.”

“You think about getting married,” said Willy. “Go home and pour that stuff down the sink and think about getting married.” Dwight seemed to nod or rock in assent. “How’d you make it anyway?”

“Gasoline and naptha flakes and stuff, common household items.” Dwight stood. Willy still expected a mystery shape, a pickled foetus or baby bat to develop in the jar. Insects preserved in amber millions of years old flew here when this was steaming jungle forest swamp. Willy watched his former classmate walk to the bus stop. He stretched his body at right angles to the lady with no left hand. He’d go to the draft board some other day, wouldn’t do on the same afternoon he talked to Dwight right in front of the Courthouse, might of been seen by the police, and his jar of jellied fancies, perverted notions, twoheaded calves, preposterosities. Preposterous the word that got him to the spelling finals what’s a good kid from Shasta Hi doing with a jar like that driving underwater in Wilson Pickett’s blue Dodge Dart through the old graveyard in the lake....

Mudfish

Next afternoon Willy wandered edgewise into Mudfish’s Psychedelic Sanctorium and Head Shoppe for no reason no reason at all, glancing behind him at passers on the street. The Shoppe’s odors made him anxious, spices of the church of the erotic, frankinstein and myrrh, abnormal fragrances, orange clove oil, sage perfume, mint body lotion, sandlewood incense, androgenous odors neither male (Old Spice) nor female (Tabu´) but alchemized from fruits and vegetables meant to be eaten not rubbed on your flesh, squeezed into polymorphous oils. Take cloves. On holidays Mom studded the baked ham with cloves. The odors conjured her in his mind, rubbing her boobs with Hormel ham. He swooned.

Mudfish was not there, then there, entered the room by brushing aside a bead curtain of the mind.

“What’s that, Mud?” said Willy, pointing at a cloud of green swirl in tubes of oilbearing glass. A bonzai whiskey still. A factory, olfactory, of perverse liquids.

“Distilled meditation,” said Mudfish, “of a Sri guru from Sufi Lanka. Mental penetration. How else you think they get it through the glass?”

Behind the counter a tourist poster displayed geese in formation over bluegreen snowtopped piney mountains, sailboats on a tourist lake, headlined CANADA, above which Mudfish had stenciled: DON’T ASK ME HOW TO GET TO.

“I don’t know, how?”

“Sweatshop in East LA. Obreros with psychoactive green syringes. Fuck if I know. Been to see your buddy?”

“Who?”

“Dwight.”

Front page of the Record Searchlight:

Police Interrogate Suspect

In Draft Board Napalm Case

“He’s not my buddy. He went and melted himself. They say the Searchlight won’t print his picture.”

“The picture they won’t print, Wilson, is the big picture.”

Mudfish fired up a nubbin of dried vegetable substance packed inside glass charts of the Copernican Universe, drew smoke through bubbling Gallo Red into his pursed lips.

“What I don’t get, Willyboy, is why he burned up files O to Q? His name doesn’t begin with O to Q. But Pickett does. Why’d he burn P? Play your cards right, P-man, you don’t have to fight Commies mano a mano.”

“He didn’t do it for me. I tried to talk him out of it for crissake.”

“There are those say otherwise. Let’s hope he doesn’t name names beginning with P.”

“I told him he was destroying property.”

“Some property has no right to exist. Zyklon-B for example.”

When Mudfish used foreign words like that Willy let them pass over.

“Dwight shouldnta done that. If the Army wants me, it wants me, if it don’t it don’t.”

“It don’t.”

“Says who?”

Mudfish palmed a card from the ether, handed it to Willy:

They don’t want you.

They don’t need you.

You have to be a fool

to die in Vietnam

Willy pushed it back across the countertop to Mudfish, who flipped it over. The flip side read:

There are two kinds of fool:

A deliberate fool.

An accidental fool.

Which are YOU?

The glass tube emanated decomposing hay, fermenting sweetgrass, stoned cows in a field of toobright daisies, technicolor corn.

“Could I have a hit off that?”

“One dolla amelican.”

Willy sucked and blinked. The arrow of geese pointed north across Butte Street. He was sure the geese used to point south. A girl he knew from Dickers walked past the window in the lightbending heat on her way to Canada.

“They do not need, they do not want, they do not use the draft for military purposes.”

“What then?”

“Follow the sound of my voice. The highest form of patriotism is suicide. Dulce et decorum est I regret I have but one pro patria morte. Right?”

“Wrong,” guessed Willie, hoping not to be.

“Boy, git this straight. I read from the text.”

A text appeared.

“The Military Selective Service Act of 1967, Section 1622.10. In Class I-A shall be placed every registrant who has FAILED to establish to the satisfaction of the local board that he is elibijul for classification in another class. I give you one chance, boy. WHAT is Class I-A?

Wild guess. “A failure.”

“I don’t hear you, chump.”

“A failure, SIR.”

“A failure to do what?”

“To establish satisfaction that he’s edible, elible, dirgeable—”

“Good enough.”

“—to get another class, SIR.”

“What does it take to die in Vietnam?”

“A I-A classifaction SIR.”

“What is death?”

“A failure to live, SIR.”

“You are not a dumb shit, Willie.”

“What kind of shit am I SIR?”

“The kind that gets stoned on one toke of fake weed. Stop staring at the geese. The problem is this country has too many Willies.”

“Got the willies, SIR.”

“Shut up. I am going to save your life.”

“Everyone must do their share.”

“Good. To fight their war they need one Willie in eleven. One Willie goes to Vietnam. Ten Willies do what? Nightwatch the hydro plant in Whiskeytown, fold shipping boxes at Ch2m-Hill, drive an ambulance at Memorial, clear trays at Shasta Community, sweep up after the revelry at Elks Lodge 1073, firewatch up on Bully Chop, register cash for Dickers. Have I got to ten? Deliver the Record Searchlight, cap bottles at Pepsi, fix transmissions in French Gulch. Then comes Willy #11, the Jumpin Jack Flash of Cu Chi, ratty hair, love beads, broken cross of peace on his mesh helmet, half a uniform, junglecrazy, drags his M-16 buttdown in the dust, jumpy as a cockroach on speed, shorttimer, been there, shot dead, flown home in a bodybag marked with a secret sign indicating that along with Willy #11’s corpse is a one-pound packet of pure Thai heroin. You know what Dwight’s face looks like?”

Willy’s continued existence required he breathe the air of the street.

“A melted frog,” said Mudfish. “Do you know there’s a draft deferment for ‘active orthodontic treatment’? A Pepsodent smile gets you out of the Army.”

You’ll wonder where the yellow went

sang Mudfish as Willy set the windchimes to clamor at the door

when they atom-bomb the Orient.

horoo

The station nurse at Redding Memorial’s Intensive Care Unit directed Willy to the office of the chief of trauma.

“Your friend — ” said the man in the office, who looked exactly like Dr. Kildare.

“He’s not my friend.”

“Then why would you endure this visit?”

“I knew him from Chemistry.”

The doctor jotted.

“Was he operating alone?”

“Operating?”

“Who were his friends?”

The doctor was padded. No. He wore another uniform under his uniform.

“I don’t know.”

“How did the knowledge of this incident make you feel? Angry? Complacent. Sad. Guilty.”

“Confused.”

“One of those four, please.”

“Sad. I think. May I see him?”

“What motivates this visit? Sympathy? Solidarity. Curiosity. Friendship.”

“I knew him from Chemistry.”

“I will be in the room with you during the time of your consultation.”

“Why?”

“Why not? Have you anything to fear?”

“Fear itself,” said Willy, amazed that he remembered the quote, that it represented his honest feelings, that he dared speak thusly to a man in two uniforms, one concealed.

Doctor Who? (he had not introduced himself) led Willie down a fluorescent corridor — past Morrie, the Redding policeman who usually directed traffic on Market; a checkpoint with a real Marine; a hospital room whose beds had been replaced by a desk, behind which sat a man in a grey suit — to a large room in the center of which an oval shower-curtain surrounded something pedestal- or altar-like. The doctor swept the curtain aside, revealing a hospital bed with something on it, flipped open his notebook.

“That’s not,” said Willy.

“Yes it is. Dwight. Your.”

“Not my friend. Not Dwight.”

Willy turned to run. The doctor restrained him.

“The black stuff,” whispered Willy.

“Magma. A semifluid mass, almost a paste. Typical of napalm burns.”

Willy breathed. He had not. He had never breathed.

The eyes on the face of the body on the table moved.

It was easy to see the eyes move because around the eyes of not-Dwight, to the width of a fist, there was no flesh but magma-bone, blackened sockets in which the eyeballs moved like the prosthetic eyes of robots at science fairs.

“Apparently,” a voice explained, “when the burning napalm splashed on his face, he rubbed his eyes with his fists, a normal reflex action that scooped the eyelids and proximital areas of tissue, already molten, away, much as an icecream.”

“Can he see.”

“What? Speak up.”

“See. Can he see.”

“Yes. Ironically that saved the sclera and cornea from incineration.”

Willy looked at Dwight’s hand nearest him; it had coagulated into a fist, dark red skin like lava .

“Whorroo,” said Dwight from unlipped teeth.

The doctor made a note.

“Hi, Dwight,” said Willy, but what he had not seen before took all his attention. Along each of Dwight’s clenched forefingers grew black, hairy, scorched but visible against the blood-red skin, eyebrows.

“Auh.” Willie choked on stomach acid in his mouth.

“Ah,” said the doctor. “You see, the follicles.”

Bristling,

“And the sweat glands. They regrow.”

but not on the skinless sockets of his brow

“And with them,”

above eyes that looked out like a drowned man’s from a well,

“the original hairs”

growing on the fists that had scoured them.

“I’m sorry,” He told the melted boy on the bed.

Nothing could keep Willy in that room.

“Horoo,” said Dwight, gently.