Just another bail hearing

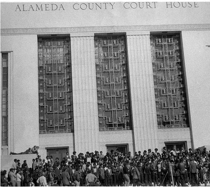

The entrance steps to the Alameda County Courthouse face away from downtown Oakland and toward the squat end of Lake Merritt, making them the front of the building by form, the rear by function. Since the arrest of Black Panther founder Huey Newton for first-degree murder, felonious assault, and kidnapping, the steps had been reinvented as political amphitheater. The daily call-and-response chorus

Revolution has come!

Off the pig!

Time to pick up the gun!

Off the pig!

of blackleatherjacketed brothers and (to one side) sisters of the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense astonished even the leaders of the Party, whose armed street theater had over-leaped itself to become a cause, a national movement, an organization, the organization, the Black Liberation Movement, The Revolution itself, all while they were putting on their shades. It dazed the New Left into a quietude that bordered on subservience, for what could white radicals do to match Huey Newton’s Revolutionary Suicide, the title of his book.

Beverly moved Jimmy’s press conference away from the chorus to a quieter side entrance. Since Huey took up residence on the tenth floor, one could get an audience at the Courthouse day or night; the press was always there.

“Why do you advocate violence?” asked the Oakland Tribune, whose offices towered over those of the judiciary.

“When we break a window,” replied Jimmy, “that is called ‘violence.’ When the government drafts 10,000 men to die in Vietnam, that is called ‘administration.’ It's not administration, it's violence.”

“Wasn’t the demonstration in which you attacked a police officer...” called out Channel 4.

“Mr. O’Shea did not attack a police officer,” said Beverly Absalom.

“... a planned violent demonstration?”

“That was an attempt,” said Jimmy, “by the-all-too-historically-meek to put an end to the violence of the all-too-historically-powerful.”

“Do you fear you won’t be able to get a fair trial in this city,” softballed the People’s World.

“What I fear,” Jimmy bunted back, “is that I will get a fair trial and Huey Newton will not.”

After which he was elevated to the 7th floor, booked, photographed, and fingerprinted while Beverly and Cathy waited in the hall outside to guide him to the bail hearing. As Jimmy wiped his fingers on his chinos, an officer motioned him to follow, led him to the counter, ordered him to empty his pockets.

“One set of house keys, one pair sunglasses,” the cop behind the counter said.

“Officer,” said Jimmy, “There’s some error here. I’m not being jailed, I’m scheduled for a bail hearing.”

“One black leather wallet, one set of car keys.”

“There’s been a delay,” said the cop beside Jimmy. “The DA got held up.”

“I can wait in the hall,” suggested Jimmy. The policeman picked his nose.

The officer behind the counter pushed forward a receipt and pen.

“Do you mind if I notify my lawyer who is on the other side of that door that I am being taken some other place than the bail hearing,” said Jimmy, loud enough he hoped to be heard through the door.

“I’ll tell him,” said the cop.

“Her, it’s a her.”

“Her. Shur.” The cop gripped Jimmy’s right elbow tightly with his left hand, guided him deeper into the building, away from the hall door.

“Excuse me, officer,” Jimmy said.

Still holding his elbow, the cop swiveled, braced, swung a practiced right hook square to the hinge of Jimmy’s jaw. Blinded by surprise, Jimmy flung his left arm against the wall; there was no pain yet.

“That’s how it feels, fuckhead,” said the officer.

Jimmy doubted that. What Jimmy felt was confusion, a desire to see familiar faces, a compulsion to maintain his dignity, an intense curiosity as to what exactly he or the cop would do next. No facesaving remark came to mind. He sensed the one punch was all and followed the cop, stumbling — his knee had hit the wall — trying not to rub his chin, to the holding tank.

“Here’s a faggot child molester for you boys,” the cop said, pushed Jimmy in.

Calling the men in the tank boys, thought Jimmy in a preternatural state of alertness, was a mistake since eight of them were black. The other two, squatting by the bars, white bikers. Plus a black man, pants down, on a toilet set in a narrow aperture in the wall. The black guys were from the street, hair conked and greased, one with biceps the size of Jimmy’s thighs. His mind flipped through a file of stupidities, Whatdya say, brothers, I’m a revolutionary, some of my best friends are Negroes, I am not now and never have been a fag childmolester, how many child molesters wear leather jackets, all power to the people. He saw himself face down in the toilet, pants around his ankles, soon as the guy in there was done. The room was 20 by 15, concreteblock and windowless. Jimmy kept his back to the bars, flicked what he hoped was a cool gaze from one face to another, seeking if not sympathy, apathy. The bikers waited to see what move the blacks made; they were not on home turf here but busting the ass of a baby raper was an acceptable interracial activity. Pain bloomed on the left side of Jimmy’s face, he shook his head no, a pitcher shaking off a sign.

“No what?” said biceps. “You don’t give it up for free?” Someone chuckled, a teenager in a hairnet, who slid toward the bars. “Turn around, boy. Let’s see your white pansy ass.”

“I’m not lookin for trouble.” Jimmy’s voice, to his surprise, came out not squeaky, high, or pleading, but almost.

“Motherfuck, you don’t have no lookin to do," said hairnet. "Trouble lookin at you.”

The man on the toilet gave a last fart, hitched up his pants, kicked the handle to flush it, came out of the niche. “What’s up?” he said.

“My black dick,” said someone near the wall.

“Faggot motherfucker,” said hairnet, “that likes boys.”

“Who told you that?” asked the man. Why is he asking? thought Jimmy.

“Pig.”

“Pig told you that and you believed him.”

“He said.”

“What is the purpose of the pig?” said the man.

“Fuck with me, far as I know,” said hairnet.

“To poison the minds of the people, Woodrow, you know that.” He turned to the bikers. “One must make a scientific investigation. On the basis of your extensive white racial knowledge, would you say this boy is a faggot child molester?”

Yes: They're familiar with child molesters. No: They’re defending one.

“He ain’t one of us.”

“Then you gentlemen wouldn’t object, on the basis of racial solidarity, if we bust his white pussy.”

“Be our guest,” said the older one.

“His pussy ain’t white,” said the younger biker, “it’s black.” The older man would have killed him then and there but for leaving him a minority of one.

“I thought all the best pussy was white, biker boys.”

Yes: They insult black women. No: They demean white womanhood.

The bikers were outclassed and knew it.

“I think I know this boy,” said the man from the toilet.

“How you come to know a faggot, Gilbert?” said Biceps.

“Maybe he’s a famous childmolester,” said the man, who had disconcerting gray eyes. “Are you famous?” he asked Jimmy.

“No.”

“If you’re famous I’d like to shake your hand.”

“Shake my dick,” said Biceps.

Everyone moved in a breath toward Jimmy. The bikers looked like they were watching a porn flick.

“Course if you’re an unknown childmolester, we turn your sick ass red. So which is it? Shake or bake?"

Shake: he has my right hand immobilized. But bake.

The gray eyes demanded.

Jimmy jammed his hand down to the joint of Gilbert’s thumb, the technique to save your fingers from being crushed. Gilbert gripped, released, slid his palm back, fingers curling, Jimmy clenched his, the fingers met, coupled, unclenched, slid forward, gripped thumbs, slid back, slapped.

“What you doing with that homo, Gil?” Hairnet looked about to cry. The bikers slouched in disgust, screen blank, film crisping. If it wouldn’t seem unmanly, Jimmy felt this would be a good time to faint.

“Trouble with you brothers,” said Gilbert, “is you don’t read the newspapers. The Oakland Tribune is an organ of the pig, the particular organ in question being the asshole, so you should not believe its oinking lies, but the least you brothers could do, if you’re not going to join the Party, is look at the pictures.”

“Yeah,” said Biceps. “What would I see?”

“This man with Chairman Bobby.” He let that sink in. “Concerning the racist and genocidal war in Vietnam.”

Unfainting, what Jimmy wanted most on earth now was his shades, which lay in a manila envelope with the rest of his possessions, so that no one could see the ready to weep total relief in his eyes and, retroactively, the fear. Gilbert had not mentioned his name, probably did not know it, so Jimmy introduced himself, shook hands with Biceps, who was named Ralph, and Hairnet, Woodrow. The others lay back, nodded their recognition, two looked away; they weren’t going to get worked up about a white boy, even an authorized one, but they accepted Gilbert’s validation. Now all that has to happen, thought Jimmy, the cells of his body still squealing, is for the black guys to be bailed out and the race traitor left to the bikers, but no, even then they were outnumbered in principle.

“Why you got to be so friendly with the whiteman?” asked one of those who looked away, staring past Gilbert.

“The color of our enemy is white, but white people are not the enemy,” he said.

Jimmy was parsing that statement when the officer who brought him in returned.

“Now the color of this man,” Gilbert said of the officer, “is white.”

Which was so obvious and free of meaning to the cop that he shuffled his feet.

“And don’t send us any more baby-rapists, officer. Unless you pay us for our work.”

“Yeah, it was rough,” said Jimmy, saluting the brethern. “If you don’t mind, officer, I’ll walk behind you.” The bruise on his cheek bloomed plumly. The policeman, still confused by being told he was white when he was white, let him.

The bruise, Jimmy explained to Cathy and Beverly in the hall, came from “that man,” but the cop was gone, the metal door clicked behind.

Mr. O’Shea, Beverly told the presiding judge, has strong ties to the San Francisco community, he is a former longshoreman, here is a stack of character references from 14 lawyers (including the well-known Willie Brown), civil rights leaders, and clergy (including the Rev. Cecil Williams), he is employed by Perini’s Foreign Car repair in a responsible position, and has no prior arrests in Alameda County.

She did not mention his arrest for trespass in Baltimore (1963, segregated amusement park), public disorder in San Francisco (1964 Sheraton Palace sit-in), curfew violation in Selma (1965 march to Montgomery), obstructing a roadway in Delano (1966 grape strike), trespass in San Francisco (1967 sit-in at DiGiorgio Grape corporate headquarters), or DUI in Mill Valley (1967 driving drunk, stoned, and on dexamil; when stopped, he asked the California Highway Patrolman what continent they were on).

Bail was set by prior agreement at $5000, collateral being the mortgage on the Napa County summer house of the parents of one Casimir Volodich, who sat in the first row.

“I didn’t know you had parents,” Jimmy said, after.

“The rumor that I’m the result of a biochemical experiment is inaccurate,” said Cosmo.

“I didn’t know your folks had a summer house.”

“Neither do they.”

The judge asked Jimmy whether he had anything to say on his behalf.

— I still do not know, he cried, What it was that I’ve done wrong.

Well, the judge he cast his robe aside, a tear came to his eye.

— You fail to understand, he said, Why must you even try?

Going to see the Man

Going to see the Man As it often looked in 1968-69

As it often looked in 1968-69