A crack in the sky

The silver pillbox lies in Jimmy’s hand. Jimmy lies on what used to be Cosmo’s big brass bed, the head of which fills the bay window. The window overlooks the Haight, the Panhandle, Golden Gate Park. Jimmy opens the apricot moonstone lid, takes out a pill the color of requited love. Two hundred fifty micrograms of lysergic acid diethylamide trapped inside the tab cross the boundary between the room and Jimmy by the opening and reception of his mouth. The bonds of pill-stuff weaken and are ripped away, the molecules of acid escape into their new room: James Fintan O’Shea. One by one they traverse the boundaries of tongue tissue, throat tissue, stomach lining, to toss among the molecules of blood (most salty sea). Gravity means nothing to them, only onrushingness. Molecule by molecule, they cross the hemato-encephalic barrier to touch the neurons of the brain.

They are far far more than molecules now. They are cause, influence, alteration, impulse, slowingness, radiance, openers, closers. No longer thing, but action, lysergic acid diethylamide crosses the last and most important boundary, if there be one, into the mind. In molecule time, it has transformed itself utterly, from object to quality, and still its new environment senses no change at all.

Jimmy feels a certain restlessness indistinguishable from anticipation. He looks at his familiar face in the bathroom mirror. The face in the mirror, or the face facing the mirror, or the relation between the two faces (mirrors are tricky) has altered. The face in the mirror is more happy than the face facing it feels. The mirror face tells the body face how to feel. The body face smiles, not catching up, the mirror face grins, keeping ahead, as the body face grins, the mirror face laughs. Jimmy has never before watched his own happiness, confronted it, enjoyed his enjoyment in quite this way, in the way that a friend would. He is friend to his face. Messages flash by sudden degrees across the bathroom sink, saying happy happy happy man, well-founded in a state of grace. Messages in light confirm, all is better than well, Jimmy is confirmed, confirmation itself is confirmed. The whiteness of his shirt praises him, praises the light that confirms the confirmation that all manner of things will be well. Praise praise.

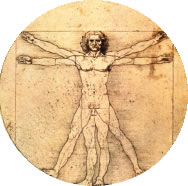

Wholer than the face in the cabinet mirror is the whole man Jimmy confronts on the bedroom wall, man as man should be, Leonardo da Vinci’s whole proportional man, diameter of the circle of the world, drawn in this room not by da Vinci but by Frank Cieciorka, an artist-friend of Cosmo’s, in the manner of da Vinci, less mathematical, more human, more bounded, more bound, Jimmy sees, in bondage to the circle of this perfection which now seems more like a medieval wheel of torture. The man on the wall is not in repose. He breathes deeply, strives against the chains of ink and charcoal that bind him to the mountainface in Scythia, not “man,” but champion of man, chained rebel Prometheus, whose chest swells in labor. He will be free. He will unbind himself from artists’ chains.

Should Jimmy help?

That depends on their relation. Is the bound man Jimmy? Who’s breathing here? Jimmy holds his breath to see if Prometheus soley breathes. The bound man breathes alone. Jimmy steps to the wall, closes an eye, sights along the wall to see if the man’s chest extends beyond. It does.

“Stay there,” Jimmy counsels the man upon the wall. He senses Cosmo watching. Cosmo is watching. Cosmo watches his every move from a photo on a table near the bed. Cosmo holds up two picket signs. One says Stop the War, the other, less legible, Jimmy somethingsomething. Jimmy somethingsomething thinks: Cosmo’s acid, Cosmo’s silver pillbox, Cosmo’s room, Cosmo’s former girlfriend in the kitchen, Cosmo’s friend’s drawing on the wall, yearning.

Jimmy turns Cosmo to the wall. “Stay there,” he orders. He hears music from speakers flanking the bed. Mozart. A piano concerto. Something occurs to him: the man on the wall breathes in concert with the concerto; the music has been present all this time, set free by persons unknown. He lies on the bed to watch the music. He has never seen such beautiful music. The music streams in stereophonic filagrees from arches on either side of the bed, from the boxes on the arches, rainboid threads of gossamoid hue depending on the instrument. Are the colors true to those Mozart experienced when composing the concerto, violins terracotta, horns blue-green algae, piano luminescent plankton riding the waves of a dark sea?

A need to verify arises in Jimmy, who does not always feel the need to verify. When he goes to a concert he does not walk among the musicians, move nearer to or further from Jerry Garcia to determine whether the notes are louder up close, weaker far away. He hears music, the music exists. He has what he needs, is satisfied.

Now he sees music, and curiosity, which is a need, breaks in. Jimmy stands on the bed, dips his hands in the music, lets its layers flow over. Freshets of music well forth from each speaker, almost meeting before they transluce, invisiblize. Pushing with his hands against the flow does not decrease, nor karate-chopping with his fingers interrupt, nor standing where the colors are absorbed by the air diminish, the spectral flow from Mozart’s mind to his. How drab, remote, invisible, music before had been! How fortunate to be offered this further sense, how cheap of God to exclude it from his endowment, how clever to bypass His restrictions, to see what could not be seen, and now, being seen, was obviously real, as his hands that glitter in the sound of struck piano wires, submerged by horns, striped by violins, are obviously real, and his, Jimmy’s.

He stands delighted, a child in a waterfall, opens his mouth to the music, drinks. The music heard continues, the music seen is gulped. He closes his mouth, the music disappears. He sucks it to vanishing, blows it to appearance. Can he redirect the flow? He inhales the stream, holds the music in his mouth, blows it across the room. No. The mighty sound resists engineering, damming, rerouting. The project of Mozart’s mind is in the place where it is, despite Jimmy. He teeters on the mattress, toward the window.

The summer’s day holds San Francisco in a dome of elation, victorian houses stream down the waterfall of Ashbury to the radiant facets of Haight, a sward of green points parkward, above it all a sky of china blue. Jimmy gasps at the beauty, the accidental, put-together, pure coincidence of all that being there in the way it is, the sport of colors with each other, the great-paintingness of his city, looked at with a wild surmise silent upon —

And it is gone.

The color.

Startled out of breath, Jimmy examines the black & white version of San Francisco below him. Of color none. The Haight and environs by Ansel Adams, Robert Frank. Pristine, but whew!

He exhales.

The color, rich as a persian rug, returns.

He, Jimmy, did it.

He breathes in. The city’s color is fixed like nitrogen in Jimmy’s lungs. He breathes out. Baghdad-by-the-Bay returns. He inhales. The colors are prisoned in Jimmy. He paroles the color out. All hues known to man remand, glorious, more glorious than before by being mixed with Jimmy’s blood.

I, Jimmy. Damn.

He orchestrates the colors, billows them in with his hands, expires them with gusts of atman, spiritus, Geist.

Jimmy plays with the arch of heaven, steals the azure from the sky, Prometheanly, returns it to the sky in bursts. Far away, how far he cannot tell, the sky cracks. A small crack, smaller than his index fingertip which he raises to cover it.

A tiny tiny tiny crack in the blue.

He yells for Hank. Hank enters from the hall. He looks small, had he been waiting there, how long?

“Hank, come here. See that? Do you see that? That over there. No, up higher up there, in the sky, the black thing like a hair, a hairline crack?”

Jimmy does not think of the hairline crack in his rib caused by a rubber sap with a cable core. For three weeks he thought of it every time he breathed. Now he has forgotten. The crack is in the sky.

“No,” says Hank.

“Why not?”

“What do you mean, why not? Cause you’re on the acid trip, man, not me. You’re supposed to see things. It’s cool.” He talks the way orderlies talk to patients. “You’re ok, aren’t you? You have what you need, right?” Jimmy looks at Cosmo’s girlfriend’s lover, which brings to mind Cosmo’s pillbox, Cosmo’s acid, Cosmo’s room. Everything has been arranged.

Everything has been too arranged.

“Can I get you anything?” says sub-arranger Hank.

“Go away, Hank,” commands Jimmy. “I don’t need arranging.” Hank dwarfs away. Jimmy looks back at the crack in the sky. The crack has grown by a hair, no larger yet than his fingernail at arms length.

Time stops. Why not? It was an artifact anyway. But, hold, a word before time starts again.

“Sky” is a category mistake and a big one. Earth is a physical entity which can be measured, dug, pounded, kicked, has boundaries. Sky does not. Sky begins nowhere, ends nowhere, has no boundaries, possesses no properties, not even blue. There is no blue up there. The sky is a “seen idea” if anything, a concept we stare up at. Sky is in the same category as horizon.

“Captain, there’s a warship on the horizon.”

“Where is the horizon, bo’s’n?”

“Right below that warship, sir.”

“Let’s hope it stays there.”

“Aye aye, sir.”

Horizon is our inability to see further. Sky is our inability to focus on air above us. Our eyes go to infinite blue focus and absently we call that ‘sky.’

A category mistake is, however, serious business. Take the category ‘Subhuman.’ Put Jews, communists, gypsies, homosexuals in that category, bind it to industrial capacities, concertina wire, railroads. Unendurable evil is released. Some pains are unendurable. Try to imagine those pains without experiencing them.

Some emotions are unendurable. What does a person do who must endure the unendurable? Breaks out of the world. A girl, head yanked backward, beefy hands around her throat, looks into the face of the last person she will ever see, her murderer, her father. Her knowledge is unendurable. Her final thoughts cannot be in the world.

Jimmy has made the worst category mistake of his life. Some thoughts are unendurable. What does a person do when required to think them? Risks mental breakout from the world.

Jimmy suspects, understands, that while the sky may not be real, the crack is.

Time wakens.

Jimmy has taken away and given back color to the world. Why stop there? What else can be taken and given? If color is ours to create and to destroy, what of the substance it is the color of? The wood and stucco of houses, leaves of trees, bark of branches, skins of people. Perhaps they too are in this world by agreement, by contract. Perhaps that settlement, that arrangement between us and the world can be discontinued.

If all there is to the sky is blue and you take that away, what is left? Look at this photo of sky by Ansel Adams. Take away the moon, the clouds. Nothingness remains. The truth about sky. The dark shines in.

Dark shines into Jimmy’s mind. His body takes over his thinking, replies to these unliveable questions by falling backward onto the bed, rigid, spasming. Separated from him his voice screams. Or a voice that sounds like his, elsewhere.

Time flees. Let it go. It never stood on its own anyway.

Parable of the Abandoned Infant:

A baby is born unwanted and placed gently in a dumpster. The evening is warm. Beyond that, there is no agreement between the baby and the world. The baby attempts to make the dumpster a habitable world, seizes the worldless forces around it, mere patches of color, swaths of smell, breaths of motion, particles of sound, waves of touch.

The infant does all this and nothing happens. The trash in the dumpster moves at the child’s touch, the child hears it crackle, grips a candy wrapper, a piece of bread, brushes its lips against a shoe drenched in root beer. There is a blanket near the child; it is not a blanket to the child and the infant cannot make a blanket of it. There is what we call food in the dumpster; the child cannot make it food. The forces around the child do not respond to its needs, remain worldless. They act as if the child were absent from the world. The child, who does everything it can, cannot engage them. The child cannot domesticate the forces around it. It inhabits an uninhabitable world, a non-world. Late the next day, the baby dies.

Moral of the parable: We make the world inhabitable, and though we imagine the world the world’s way, we only inhabit the world we imagine. The abandoned baby could not imagine a world in which it could continue to live.

Time returns.

Someone who says she is Edna sits on the bed next to Jimmy, lays soft hold of his rigid arm. “May I sit here with you?” she asks.

“Please.” Her hand on his arm is flesh. Jimmy’s body decides to accept her, to leave to her the making of his world inhabitable. He opens one eye, looks at Edna. Spiders are her hair. He shuts his eye. There are still people in the world even if spiders are their hair.

Time’s bones break.

Jimmy’s mind is overrun by rabid cartoon figures and their parts, their babble and woohoos. They make no sense at all. But since there’s always room for another thought, even a frantic thought about frantic thoughts, Jimmy wonders if what sanity mostly does is keep this population of gibbering sketches and crude outlines at bay. Perhaps Mad Meg looting at the mouth of Hell is our sanity, grabbing what she can that is useful, valuable, and makes the world inhabitable, while her housewife warriors hold back the screaming fishheads, asshole mouths, mickey mice, birds in helmets, eggs with knives, self-swallowing orifices, killer rabbits, on the bridge between the bridge between the bridge between.

Time’s fractures heal.

Jimmy’s body’s decision to close its eyes is wellfounded. The bridge on which Jimmy’s mind stands (beneath the pillars of which millions of born and unborn have been sacrificed to keep it from collapsing) connects perception and imagination, the world of sense and the world of thought. Jimmy has lost his balance in the world of sense. Why does his rigid body shake like a rung gong? He is shaking off his senses.

Jimmy’s body, a true philosopher, acts wisely. How does something come into experience? Eyes, ears, nose, throat, and skin. They have betrayed him, or else they are true and the world false. Either way, he counts on his body for the truth. Are those pearls that were his eyes? Are those spiders that are her hair? I can no longer verify, the body says. Don’t ask me to reach out, touch, smell, taste. I will not flick Edna’s auburn hair with a finger to see if it crawls back to her head. I will not look deeply into her eyes and tell you they are pearls, that Edna, on whom you depend for your survival, abandoned child, hath suffered a hell-change. Leave me behind. I sacrifice myself for you. I that was your opening to the world shall be your wall, your fortification of dense stone, your un-feeler.

Therefore. Oh-ooga! Oh-ooga! Ahab, the submarine commander, orders the flooding compartments sealed. Firewall! Firewall! Set the backfire, burn out the underbrush. Send the Rome Plow through the scrub oak and chapparel. Shut the mother down! Jimmy’s rigidity is the steel of the submarine, his tremors the oogah of siren. Going under.

Ahab in a submarine, Mad Meg on the bridge to Hell, firewalls, burn zones?

—Permission to mix metaphors, Captain.

—Granted, bo’s’n. Where be they so necessary for accurate description as on an acid trip?

—Truth, Captain, where that boy’s headed, one must be in two places at once.

He crosses the bridge to hell. Mad Meg holds his abandoned senses in a silver chest with an apricot moonstone lid. Armed and brave, she defends the world of pots and spoons and tables and the smell of lilac. The housewives of reason hammer and flog the agents of turbulence, disorder, fluid dynamics that lie below consciousness. Mad Meg’s back is to him. She withers to a cartoon. Only her edges show. Already Jimmy sees objects before they appear, the unformed, eyeless thoughts, the language below words.

Running deep, he is not safe, but saved. He leaves behind the question of spiders, color in the world, cracks in the sky. He has deserted perception and its unreliable reports and entered the only other world there is, the one he imagines.

Time rises, time sets.

Jimmy lies deep in his mind. Real as a dream, he dreams himself safe from the world his body lies in, cared-for and soothed by a human woman in some form. Here, what is, IS. There is no doubt. He encounters a school of Mussolini-headed cephalopods. So be it. They swim by. He fears them, but not as he would in the perceptual world, for being. He does not have to search the horizon for warships. There is no horizon. There is no furthest he can see. If there is a warship, it is there. He does not worry whether he is upright or fallen; he cannot trip on anything. He does not fret over what that shadow might be or what creature may have cast it.

Everything is exactly what it seems. Nothing turns out to be anything but what it appears to be. Nothing has a hidden side. Nothing is treacherous. No one can betray him. Balance is restored.

Take Johnny Cash for example. Here is the Man in Black. Instantaneously here, with no need for explanation. Not a faraway figure, unclear as to who he may be, then walking nearer, recognized, verified (Hi, I’m Johnny Cash). No, JC is right here, in the same jail cell as Jimmy, in a prison somewhere in the Old Southwest.

Up above, in the treachery of Cosmo’s living room, if Jimmy opened his eyes and saw Johnny Cash on the bed — surprise! You’re crazy! Or some explanation would be required. Down here, silent running, he’s in the cell because he’s in the cell because he’s in the cell.

“Listen, man,” says Johnny in his lanky bass, “Let’s blow this joint.”

“I’m with you.”

Next thing, and there can be no doubt it can be the next thing, since in the mind the next thing is whatever the next thing is, Jimmy and Johnny are horsewhipping a stagecoach across the burning chaparral, the posse eats their dust, banjoes play that prison breakout hoedown celebration stomp. The posse drops behind. They’re free. They holler. They sing.

I hear the train a-comin

It’s rolling round the bend

And I ain’t seen the sunshine since

I don’t know when

It crosses Jimmy’s mind, the mind that is Jimmy’s on the driver’s rattling stagecoach seat, Johnny riding shotgun, that the posse could appear suddenly ahead of them dropping from the sky. The thought fleets. Nothing here surprises because nothing here can be anticipated, therefore nothing unanticipated (a surprise!) occurs. We’re free.

Time keeps draggin’ on.

The philosopher saith, “The content of our imagination is exactly what we imagine it to be; nothing more; nothing less, for there is no such thing as an illusory imaginary object.”

— Run that past me again, Captain.

— Certainly, bo’s’n. There is no such thing as an illusory imaginary object.

— Steady as she goes, sir.

— We will mock no philosophy on my ship. We have no illusions down here, man, no illusions, I say. For how can what the mind imagines not be what it is. If I imagine a white whale, the whale is imagined, it cannot be illusory, for I have imagined it. Imagine something.

— Me and my lady, sir, by a warm hearth.

— Was that image a true image or was it false? Was it in your head, man, or were you deluded into thinking it was in your head?

— It was true, Captain, true as the meridian, true as she goes.

— You are a practical fellow.

— Begging your pardon, Captain, but when we rise to the surface, what then?

— Contradictions, sir, contradictions.

Time rises.

“Jimmy. Jimmy?”

“Yes.”

“Hank’s been calling all over the city. Who do you want to come be with you?”

“You mean whose friendship do I want to destroy?”

She laughs. A warm sound. I ain’t heard laughing since I don’t know when.

“How long has it been?” asks Jimmy.

“Five hours.”

She lies beside him. He feels her pouch-shaped body, hears the clack of her beak.

Dive, dive.

Time falls.

Jimmy’s arms and legs have quieted, their spasms eased, the bodyquake transferred to his torso, its contractions and expansions taking on an esophogeal character, increasingly rhythmic and coordinated, rippling from his chest downward toward the pelvic area. He presses his arms flat against the bedspread, braces for the next surge of contractions. Inwardly, his muscles convulse wave on wave, the swell and gush of harbor waters against the mud and bones of piers. Bobbing boatlike in his entrails, below the stomach of hunger, another stomach of fullness overfilled. A desire to push outward swells his lower body, a complex surging of the bowels, or rather some cavity not stomach-like nor intestinal nor rectal, an occupied opening in need to burst forth, evacuate. The ripples create a kind of sonar, he travels inwardly as on the echolocation screen of a submarine. Gradually, his muscles feel their way toward explanation. Their flicker and retreat chart unknown walls and chambers of his body, locate a second pulse within him, lightly firm, quicker than even his own anxious heart, a lower, smaller heart within, a pulse in the cavus of his groin, the flutter of tiny extremities taking up his own stilled tremors, the kick of a swimming creature, the bump and drift and bump of a boat at harbor in a swell, bump, rise, fall. The kicks pelt his stomach, the hand-flutter vibrates lower down, and in his groin the swelling like a thickening gourd, or head, for it is a head, a human head, seeks the widening of his altering genitals, the stretch of an unknown orificium. He feels a terrible concentration, the deep need to bear down, to be borne away. He feels no pain, yet cannot endure for long.

The infant, a boy, it has always been a boy, bores through the quaking channel that is Jimmy, bears to the light, toward the surface of the world Jimmy has abandoned. A rush of need more intense than pain or love propels him out, onto the bed of the material universe. He stands on one leg, hops, smiles at his father, leaps into the dangerous world, laughing.

His father must follow him. Jimmy opens his face wide, seeks him, agape.

“What was that?” asks Edna. Her hair is hair, her face shell-like, fragile, her body at some uncertain risk.

“That’s the most amazing thing that ever happened to me,” says Jimmy.

“You’re crying. You were crying.”

Jimmy moves his hands on purpose for the first time, smears salty wetness across his face.

“I gave birth to a baby. I had a baby. Did you see him?”

“He was a boy?”

“Me, I think.” Jimmy laughs, laughs, shakes, takes Edna’s hand. “You didn’t see him?”

She didn’t.

“He was in a hurry,” says Jimmy. “He danced and got on with it. That was the goddamndist thing.”

“Congratulations, Dad,” says Edna. “You want some water?”

He nods. The water is there, has been there for when it was needed. He gulps it down. The room has been cleansed, scoured with light. Too much light. Da Vinci’s perfect man hangs lifeless, crucified on a cross of art; Jimmy sorrows for his failure to escape. He should have hooked up with Johnny Cash, one needs a partner.

Cosmo’s room is too new, too fresh from the factory of creation, has not been lived in, has no history yet. They forgot to build in age, thinks Jimmy, some path by which it came to be. If the door slams, do the walls teeter? Are they painted only on this side? Do stage hands linger at their ropes behind plywood and canvas?

Time bears down.

“I’m going back,” he says, closes his eyes.

The ability to transform ourselves, reversibly, from perceiver to imaginer and back, is what we are. We flit from being in the world to having the world inside us. Jimmy is not himself yet. He fears, has just feared, looking on Edna, fragile as trust, that he only imagined opening his eyes, imagined his rising to the surface, imagined his conversation with Edna, imagined drinking water (feigned water in a stage glass), and now, eyes closed, has never been but eyes closed, and how can he know? How will he know when he perceives a lovely world that’s real and not a too-bright performance for an audience of one?

Time lightens up.

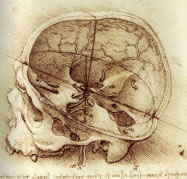

Behind the lovely world there is another, which Jimmy may not know. The lovely world is delivered by the five doctors, eyes, ears, nose, throat, and dermatology. Else is forbidden. The doctors pre-scribe, “write before,” what Jimmy may know. They write down what Jimmy may see before he sees it, what he may touch before he touches, and so on. By the very fact that the doctors exist, he knows the “senseless” world is out there, the world the doctors don’t tell us about, for their prescriptions are sparse, diaphanous and meager. They are so stingy we should all die from lack of sense. But no, Jimmy is arrogant beyond sense. He knows he can’t touch atoms, see x-rays, but he believes in magnifiers. He unpacks his boy’s kit of magnifiers, stands in the path of x-rays, studies the plate they land on, studies the hairline crack in his rib put there by tangible energy at the end of a real cop’s sap, thinks I have x-ray vision, not by birth but by science, boy, am I a whiz!

Foolish boy! He has no x-ray vision. He sees pictures painted by particles on metal plates. He sees them in light he can see, the narrow, pallid office light that sprinkles the world, the pencil flashlight he sees by. He looks at the x-ray plate and should be terror-stricken, should fall on his knees in abjection, moan in fear.

He’s looking at a copy of the universe. And there is no original.

All his vaunted magnifiers, microscopes, telescopes, stethescopes, microphones, television, make only bigger copies. Some magnified points appear as galaxies, others as electrons. These pictures too are only copies.

And there is no original.

If that doesn’t scare you, nothing will.

Jimmy gets down to cases. In order to make life bearable, he conspires to read the doctors’ five prescriptions as being, not in him, but in the object they prescribe. They prescribe an apple, a nice, juicy, firm, sweet, glossy, crunchy, red apple. And up until this moment, in bed in Cosmo’s room, lying next, he hopes, to Cosmo’s former girlfriend, Edna, caretaker of his corporal existence, he has been happy as a mark being taken by the sharpest con in the biz to think that the nice, juicy, firm, sweet, glossy, crunchy, redness of the apple is somewhere IN the apple.

Now that’s gone. The mark is hip. The molecules of the apple, O marks of the world, are neither nice, juicy, firm, sweet, glossy, crunchy, nor red. Not one.

And yet.

There is an apple there. Isn’t there? The five doctors say there is. They are the ultimate authority. Jimmy has doubts about authority.

Jimmy has a vision, as close to religious as he will ever get. He came to it by swallowing all the color in San Francisco and breathing it out.

The vision is this. Through everything we know, through our lovely, juicy, firm, sweet, glossy, crunchy, colorful existence, flow the dark, blind, and worldless forces that are the world without us in it.

In that world, rivers are not wet, leaves not green. Stars are neither bright nor dim, nor large nor small, for there is no scale with which to measure them. Stars are not hot and the space around them not cold. There is no measurement at all, no point of view. Loveliness is not.

All there is in Jimmy’s world is what he senses and what he imagines. Total acts of faith. Jimmy sits up, watered in sweat. He looks at Edna’s face. He has faith that the back of Edna’s head is there.

“Could you turn your head around?” he asks. She does. The back of her head is there.

“Now look at me.” She turns. Her face is there. But for a moment, a snap of a moment, a false moment perhaps, the front of her head is not, and Jimmy sees only brain and bone and cavities and blood vessels, as if a pane of glass had fallen, slicing her skull in half and holding there, a half-head laminated under the threshold of Jimmy’s knowing, somehow known.

“You’re lovely,” says Jimmy.

“Are you ok? I mean, thank you.”

“How long has it been?”

“Seven hours. It’s almost nine. I have to go to work.”

“Where?”

“A strip club on Broadway.”

“I never knew that.”

“The pay’s good, that’s where the rent comes from.”

“Thank you for doing whatever you did for me the last seven hours.”

“Hey, you had a bad trip. It happens to everyone. Hank’s in the kitchen.”

Jimmy is still sitting cross-legged on the bed when she pops in on her way downstairs, wearing a leather miniskirt and fishnet blouse.

“Bye,” she says.

“Bye.”

Time lightens up.

Captain Ahab surfaces at the mouth of hell. The rivers run powerfully there. Perhaps the boat top center in Bruegel’s Dulle Griet, suspended on the shoulders of a man in crustacean folds, digging what? from his asshole with a ladle, is the Pequot. Who knows where it went when it drowned.

Jimmy pushes his way through the brutal housewives back across the bridge to the mainland of perception, which he now knows to be the wasteland of just-as-much-reality-as-he-can-stand. He avoids touching the walls of the hall to Cosmo’s kitchen. He sees two hands holding a San Francisco Chronicle. On faith he assumes there is a person behind the paper attached to the hands, and that person is Hank.

“Hank?”

The hands lower the paper. The object attached to them looks like the anterior plane of the man he knows as Hank.

“Welcome back,” says the Hank-person. Jimmy does not ask him to turn around. Faith will do.

“Want some soup?” asks the Hank.

Jimmy does not trust him but he needs soup. Hank ladles out a Mexican bowl of lentils from an iron pot on the stove. They resemble what the man beneath the Pequod ladles from his ass, but Jimmy’s too hungry to care. He can’t tell Hank how frightened he is. He can’t tell Hank that all we know in the world are sensations and thoughts about sensations. He can’t tell Hank we are all abandoned infants. He can’t tell Hank that to stay sane we have to take on faith that the lovely world we sense is real, and all we know is a shaky xerox of an original that doesn’t exist.

He can’t tell Hank that the dark lifeless reaches of space are not out there. They’re here, in the table where they sit. IN THE CHAIR, HANK, THAT YOU’RE SITTING ON. The expanses of emptiness, the terrible reaches are IN US. Here in the kitchen.

Instead, he swallows the soup, which is more important than knowledge.

Hank pushes a cut-glass tumbler of Mountain Red toward him. On the first sip — is the knowledge in the wine? — he knows where he will be safe. He is amazed. He is not surprised. Nothing in his imagination can surprise.

“I’m going to Shauna’s,” he says.

“You sure? I’m not so sure that’s”

At the top of the stair, Jimmy grips the balustrade for balance. The walls are papered in vividly faded flowers. I assume there is something behind them. I hope, god, do I hope! Please God In Whom I Don’t Believe, let there be ink behind the colors, let there be paper behind the ink, let there be glue behind the paper, plaster beyond the glue, wood lathing under the plaster. Let what I see mean something. He takes the stairs like an old man in a rush. At any moment, if he slips, if his hand brushes the wall, the ripping paper will rend space and reveal inside the wall, behind the paper — the black outer reaches and the unlit stars.

The Ashbury Street hill does what the Ashbury Street hill does when molecules of lysergic acid diethylamide break down and disperse. It holds up its end of the settlement between Jimmy and the invisible world, allowing him to walk ten houses down to Shauna’s without spilling into the void. He raps on the cut-glass door.

Because the world is round, Shauna is there. She too was called by Hank.

“You might as well have been on the evening news,” she says, “come upstairs.” He follows her to her bedroom, which is, like her, elegant. He lies on the lace coverlet of her bed, pries off his boots. She lights candles on the sideboard. She brings him wine and a sandwich.

“You can’t stay the night,” she tells him.

“I know.” He watches the ghosts of pastel caterpillars hump along the moulding. “You’re the only person in San Francisco I completely trust.”

She lies next to him, propped on an elbow, the lace of her dress folded into the lace of the spread.

“I am your friend,” she says. “I am always your friend.”

The gun in her purse. The gun pushed across the car seat in the Alabama night. The words Ok my love.

“I love you,” says Jimmy.

She twines his hair with her fingers, tucks a strand behind his ear.

“I won’t hold you to it,” she says.

He sees her in lace and armor, looting at the mouth of hell.